Recommendations and Advice

"Houston Fredericksburg, we have a problem."

Recognizing and resisting the “Normalization of Deviance” is the theme of this blog. It happens in organizations as small as single airplane skydiving operations to those as vast as the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Even agencies and organizations tasked with making aviation and sport parachuting safe are susceptible to it.

The investigations of fatal aviation accidents provide multiple examples of how the normalization of unsafe practices play a role in the loss of life. They can also reveal how those who accept the responsibility to investigate those accidents and suggest or devise ways to prevent accidents in the future can themselves fall short.

Oahu Parachute Center Accident, June 21, 2019

The accident in Hawaii on June 21, 2019 when ten skydivers and the pilot were killed and most, if not all tragedies of its type, demonstrate deficiencies that exist up and down the chain, from the operators, to the investigators and finally with those who seek to formulate the remedies.

The National Transportation Safety Board’s (NTSB) investigation of the events at the Oahu Parachute Center (OPC), which was published in January of 2021, found numerous conditions that contributed to the accident.

NTSB Conclusions About the Accident

In Section 3, “Conclusions” of the Accident Report, the NTSB found that:

1. After making an intersection takeoff, the pilot conducted an intentional aggressive takeoff maneuver involving a low-altitude high-bank turn and simultaneous pitch-up maneuver.

2. The airplane was likely operated near or possibly beyond the aft center of gravity limit during the accident takeoff.

3. The pilot’s aggressive takeoff maneuver caused an accelerated stall and a subsequent loss of control at an altitude from which recovery was not possible.

4. The twisted left wing that resulted from the airplane’s previous accident reduced the airplane’s stall margin, which likely caused the left wing to stall before the right wing and precipitated the airplane’s roll to the left.

5. The pilot’s initial training did not provide him with adequate experience and proficiency for Beech King Air operations.

6. By indicating that the accident pilot completed dual commercial flight instruction that he likely did not receive and by not providing initial training according to established standards, the pilot’s flight instructor showed a lack of professionalism and a disregard for aviation safety.

7. The Beech King Air 65-A90 flight training that Oahu Parachute Center provided to new company pilots was insufficient and did not ensure that the accident pilot, who lacked training and experience in the airplane make and model, was prepared for the company’s parachute jump operations, which included the operation of the airplane near its aft center of gravity limit.

8. The accident airplane was not airworthy because (1) it had not been properly repaired after the previous accident and (2) Oahu Parachute Center and its contract mechanic did not maintain the airplane in an airworthy condition.

9. The airplane’s maintenance records were not kept in a manner that was consistent with the requirements of pertinent federal regulations.

10. Oahu Parachute Center’s failure to address a safety hazard involving the airplane used for the company’s parachute jump operations, inconsistencies with applicable federal regulations, lack of standard operating procedures and structured pilot training, and flawed method for calculating the airplane’s center of gravity demonstrated the company’s inadequate safety management.

11. The tandem instructor’s and the camera operator’s use of marijuana before the accident flight demonstrated their lack of judgment and professionalism given their safety responsibilities for the accident flight.

12. Even though Federal Aviation Administration inspectors accomplished the inspections of Oahu Parachute Center that the agency required, those inspections were insufficient for ensuring the safety of this commercial passenger-carrying operation.

The Board concluded that the probable cause of the accident was:

. . . the pilot’s aggressive takeoff maneuver, which resulted in an accelerated stall and subsequent loss of control at an altitude that was too low for recovery. Contributing to the accident were (1) the operation of the airplane near its aft center of gravity limit and the pilot’s lack of training and experience with the handling qualities of the airplane in this flight regime; (2) the failure of Oahu Parachute Center and its contract mechanic to maintain the airplane in an airworthy condition and to detect and repair the airplane’s twisted left wing, which reduced the airplane’s stall margin; and (3) the Federal Aviation Administration’s (FAA) insufficient regulatory framework for overseeing parachute jump operations. Contributing to the pilot’s training deficiencies was the FAA’s lack of awareness that the pilot’s flight instructor was providing substandard training.

Special Investigation Report SIR-08/01

In 2008, nearly thirteen years prior to the publication of the report on the crash in Hawaii, the NTSB published a landmark Special Investigation Report, number SIR-08/01. That report was the first summary of accidents involving skydiving operators. It looked at 32 accidents since 1980 that killed 172 people, most of whom were jumpers.

By the numbers, the salient points are:

- 12 of the 32 accident airplanes were loaded beyond their maximum gross weight. Nine of those aircraft were loaded outside their cg limits.

- 11 of the 32 accident airplanes lost engine power shortly after takeoff

- 10 of the 32 accident airplanes stalled and/or experienced loss of control

- 8 of the 32 accident airplanes were not airworthy at the time they were dispatched.

- 4 of the 32 accident airplanes were powered by engines that were operated beyond their manufacturers’ recommended TBOs

- Most accident airplanes had maintenance or fuel quality deficiencies

- In nearly all of the 32 accidents reviewed the pilots were deficient in basic airmanship tasks.

- 16 of the 32 fatal parachute operations accidents occurred after the FAA issued inspection “requirements” in Notice 1800.134. These 16 accidents claimed the lives of 77 people.

Common Factors

The contributing factors for the event in 2019 in Hawaii were broadly the same as those in the accidents between 1980 and 2008. In the press conference following that tragedy, NTSB board member, Jennifer Homendy said the crash was one of eighty since 2008 involving aircraft that were engaged in skydiving operations. Those accidents took nineteen lives and again, most, if not all of those events involved many of the same contributing factors as those reported in 2008.

Obviously, 2008 is a departure point to the NTSB. At that time they made recommendations that they hoped would make flights made for the purpose of skydiving safer. Summarizing the accidents after 2008 into another report won’t be complete if it doesn’t look into why the actions taken in response to the recommendations of the first report were ineffective.

The NTSB investigators are skilled professionals with considerable resources. The report dockets include anything that anyone wants to submit so it’s safe to assume that their report, along with all the other published submissions, is pretty much the whole story of the accident. That’s not to say that their efforts are perfect. Obviously, they are not.

Conceivably, the FAA could have prevented all these accidents, but not without a much more vast and unacceptably more expensive bureaucracy.

In all single vehicle automotive accidents the fault lies primarily with the operator of the vehicle and with those most directly associated with that vehicle’s operation and maintenance. Therefor most of the blame lies with the pilot and most of the time he’s among those who pays the ultimate price, so this won’t be so much about him, or her. It’s intended for individuals other than the pilot, who are available after the crash, and the organization who could help prevent accidents in the future, namely the drop zone operators, the United States Parachute Association and the jumpers that weren’t killed.

How the System Is Intended to Work

The current system isn’t working for skydiving so a description of how that system functions comes first.

From their investigation the NTSB draws conclusions about why each transportation accident happens and makes recommendations for how to prevent them. For skydiving operations, their recommendations are made to either the FAA or the USPA. The NTSB then tracks what’s done about the recommendations in a database. It’s called CAROL , Case Analysis and Reporting Online. The NTSB’s Special Investigation Report from 2008, number SIR-08/01, resulted in Recommendations A-08-63 through A-08-074.

Although the records in their database doesn't include a comparable field, the twelve recommendations fell into four categories: Aircraft Airworthiness, Piloting, Surveillance (by the FAA) and Restraints (seat belts).The status for each of the recommendations follows:

| Number: A-08-063 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 12/12/2014 | Status: UNACCEPTABLE ACTION |

| TOPIC: Airworthiness, RECOMMENDATION: To the FAA - Require parachute jump operators to develop and implement Federal Aviation Administration-approved aircraft maintenance and inspection programs | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: The Official Correspondence between the NTSB and the FAA consisted of seven messages from January 15, 2009 until December 12, 2014. The FAA’s final response, dated October 28, 2013, read, “. . . we cannot legally require an owner/operator to unilaterally adopt manufacturers’ recommended maintenance instructions. However, we encourage operators to voluntarily review and incorporate such instructions. Nevertheless, we maintain that the requirements of sections 91.403 and 91.409, along with the guidance provided by the United States Parachute Association, satisfy the safety concerns identified in this recommendation.” In their final Official Correspondence the NTSB noted that the “manufacturers recommended instructions” is not the only method by which an acceptable maintenance program could be established. The NTSB also pointed out the FAA did impose additional FAR Part 91 requirements for Fractional Ownership Operations Part 91 Subpart K published in 2003). That subpart was far more complicated and extensive than what would be needed for skydiving. | ||

| Number: A-08-064 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 05/23/2013 | Status: ACCEPTABLE ACTION |

| TOPIC: Airworthiness, RECOMMENDATION: To the FAA - Develop and distribute guidance materials, in conjunction with the United States Parachute Association, for parachute jump operators to assist operators in implementing effective aircraft inspection and maintenance quality assurance programs. | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: The USPA (1) developed and distributed to all Group Member Drop Zone operators an aircraft maintenance guidance packet, clarifying which FAA regulations apply to jump plane operators and explaining the inspection and maintenance options available, (2) amended its Basic Safety Requirements to verify that all aircraft used for parachute operations comply with the commercial maintenance requirements described in FAR Part 91.409 (a) through (f), and (3) verified that all its member operators are complying with the amended requirements. | ||

| Number: A-08-065 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 6/16/2011 | Status: UNACCEPTABLE ACTION |

| TOPIC: Piloting, RECOMMENDATION: To the FAA - Require parachute jump operators to develop initial and recurrent pilot training programs that address, at a minimum, operation- and air craft-specific weight and balance calculations, preflight inspections, emergency and recovery procedures, and parachutist egress procedures for each type of aircraft flown. | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: From their first Official Correspondence dated March 12, 2009 the FAA contended that no additional requirements were needed to ensure the proficiency of jump pilots. The final “Official Correspondence” dated March 8, 2011 from the FAA to the NTSB stated that there was no evidence that jump pilots lacked necessary skills, only that those skills weren’t demonstrated. AC 105-2D, "Sport Parachuting", was pending at the time of this correspondence. The March, 2011 Correspondence was from J. Randolph Babbitt, FAA. Mr Babbitt stated the FAA’s final position. Mr Babbitt wrote, “This AC will bring a higher awareness of the typical and avoidable accidents that involve jump aircraft. The revised AC will not only make the jump pilots and drop zone operators more aware, but also the parachutists who board their aircraft. I will provide the Board with a copy of AC 105-2D when it is published. At that time, I will consider Safety Recommendations A-08-65 and -66 closed.” | ||

| Number: A-08-066 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 07/23/2015 | Status: UNACCEPTABLE ACTION |

| TOPIC: Piloting, RECOMMENDATION: To the FAA - Require initial and recurrent pilot testing programs for parachute jump operations pilots that address, at a minimum, operation- and aircraft-specific weight and balance calculations, preflight inspections, emergency and recovery procedures, and parachutist egress procedures for each type of aircraft flown, as well as competency flight checks to determine pilot competence in practical skills and techniques in each type of aircraft. | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: The supporting Official Correspondence for this recommendation are the same as A-08-065 | ||

| Number: A-08-067 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 07/23/2015 | Status: ACCEPTABLE ACTION |

| TOPIC: Piloting, RECOMMENDATION: To The FAA - Revise the guidance materials contained in Advisory Circular 105-2C, "Sport Parachute Jumping", to include guidance for parachute jump operators in implementing effective initial and recurrent pilot training and examination programs that address, at a minimum, operation- and aircraft-specific weight and balance calculations, preflight inspections, emergency procedures, and parachutist egress procedures. | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: AC 105-2C was issued in 1991. AC 105-2B, dated August 21, 1989, was not distributed. The original Advisory Circular for Sport Parachuting, 105-2 was released in 1968. | ||

| AC 105-2D is dated May 18, 2011. | |||

| The current AC for Sport Parachuting, AC 105-2E , is dated December 4, 2013. Section 8.b in that AC includes the revisions called for in the Recommendation. In the FAA’s Official Correspondence to the NTSB dated October 9, 2010 it’s stated that, “USPA agrees with the FAA that current regulatory requirements for inspection and maintenance must be better communicated and disseminated. USPA will educate aircraft owners, pilots, and DZ operators by using the association’s monthly magazine, email, and website, as stated in their response to this safety recommendation (enclosed).” | |||

| Number: A-08-068 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 07/18/2012 | Status: ACCEPTABLE ACTION |

| TOPIC: Surveillance, RECOMMENDATION: Require direct surveillance of parachute jump operators to include, at a minimum, maintenance and operations inspections. | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: Order 8900.1, “Flight Standards Information Management System,” Volume 6, Chapter 11, Section 5, was revised on August 1, 2011, to include maintenance and operation inspections, aircraft configuration authorization, flight manual supplements, placards, operational waivers, pilot certification and training, and parachute airworthiness. Order 1800.56, “National Flight Standards Work Program Guidelines,” was revised on July 21, 2011, to include surveillance of any parachute operation aircraft under Part 91 conducting parachute operations in accordance with Part 105. We note that an Aviation Safety Inspector must choose at least 1 airworthiness inspection and 1 operations inspection from a list of 10 inspection types (for example, 1 maintenance spot inspection and 1 operations ramp inspection). These revisions satisfy the intent of the Safety Recommendation. | ||

| Number: A-08-069 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 10/19/2011 | Status: EXCEEDS RECOMMENDED ACTION |

| TOPIC: Airworthiness, RECOMMENDATION: To the USPA - Work with the Federal Aviation Administration to develop and distribute guidance materials for parachute jump operators to assist operators in implementing effective aircraft inspection and maintenance quality assurance programs | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: By developing and distributing an “aircraft maintenance guidance packet” to all group member drop zone operators the NTSB deemed the USPA’s actions to be “outstanding” and to have exceeded the recommended action. | ||

| A-08-070 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 02/13/2012 | Status: EXCEEDS RECOMMENDED ACTION |

| TOPIC: Piloting, RECOMMENDATION: To the USPA - Once AC 105-2C, "Sport Parachute Jumping", has been revised to include guidance for parachute jump operators in implementing effective initial and recurrent pilot training and examination programs that address, at a minimum, operation- and aircraft-specific weight and balance calculations, preflight inspections, emergency procedures, and parachutist egress procedures, distribute this revised AC to your members and encourage adherence to its guidance. | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: Publication of FAA AC 105-2D served to meet this NTSB Recommendation. USPA subsequently distributed the revised AC to its members (via e-mail) and published two articles in the USPA monthly magazine Parachutist to encourage jump aircraft operators to adhere to the new AC guidance. Consequently, Safety Recommendation A-08-070 was classified “Closed—Acceptable Action” on October 19, 2011. In their Official Correspondence dated February 13, 2012 the NTSB wrote, “We note that the USPA has also urged operators to enhance their jump pilot training regimen and has developed and included in the 2011 USPA Skydiving Aircraft Operations Manual and the Jump Pilot Training Syllabus additional guidance on pilot training and proficiency. We believe that these additional actions are responsive and go beyond the scope of Safety Recommendation A-08-70.” Accordingly, the recommendation is reclassified CLOSED—EXCEEDS RECOMMENDED ACTION. | ||

| Numbers: A-08-071 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 3/6/2012 for A-08-071 and -072 and 10/19/2011 for A-08-073 | Status: ACCEPTABLE ACTION (for all three) |

| A-08-072 | |||

| A-08-073 | |||

| TOPIC: Restraints, RECOMMENDATION: A-08-071 and A-08-073 recommended that the FAA and the USPA conduct research to determine the most effective dual-point restraint systems for parachutists that reflects the various aircraft and seating configurations used in parachute operations. A-08-072 and A-08-074 recommended that Advisory Circular 105-2C be revised to include guidance information on installing and using the new restraint system. | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: FAA’s Civil Aerospace Medical Institute (CAMI) in Oklahoma City, analyzed the results of sled tests of restraints used in various aircraft configurations. The USPA summarized the information contained in AC 105-2D regarding the seats and restraint systems recommended for parachutists and included this information in multiple USPA publications. They encouraged operators and skydivers to follow best-practice guidance for the use of restraints in skydiving aircraft. As a result of the USPA’s actions, Safety Recommendations A-08-73 and -74 were classified “Closed—Acceptable Action” on October 19, 2011. | ||

| Number: A-08-074 | Date Issued: 09/25/2008 | Date Closed: 2/13/2012 | Status: ACCEPTABLE ACTION |

| TOPIC: Restraints, RECOMMENDATION: Once an effective restraint system is determined, educate USPA members on its use. | STATUS JUSTIFICATION: The USPA also featured two articles in Parachutist on AC 105-2D which encouraged operators and skydivers to follow best-practice guidance for the use of restraints in skydiving aircraft. These actions were sufficient for the NTSB to classify the Recommendation “CLOSED—ACCEPTABLE ACTION”. | ||

The Special Investigation Report (SIR-08/01) included an Introduction, an Appendix and these other sections:

- Background

- Maintenance Issues (Airworthiness)

- Pilot Training and Proficiency Issues (Piloting)

- FAA Oversight and Surveillance Issues (Surveillance)

- Conclusions

- Recommendations

Survivability, or the need for better Restraints, is in Appendix A of the report.

How the Current System is Failing Skydivers

Although the factors cited in each of the accidents reviewed in The Special Investigation Report (SIR-08/01) are known, and recommended solutions have been implemented, accidents that are the result of the same factors persist. In reviewing each of the recommendations from the report it’s fairly clear why that is the case.

Airworthiness Recommendations from the NTSB Report SIR-08/01

Recommendation A-08-063 was to improve the airworthiness of jump aircraft by requiring better aircraft maintenance. Requirements are accomplished through regulation. The FAA, the USPA, the drop zone operators, pilots and most skydivers know that regulations can be rather blunt instruments that can have unintended consequences. The NTSB classified A-08-063 as, “CLOSED - UNACCEPTABLE ACTION” because the FAA determined that increased regulation was not called for. They didn’t disagree that better maintenance is needed but they didn’t agree that more regulation was the answer.

Recommendation A-08-064 is the same as A-08-69. Both recommend the FAA and the USPA work together to improve the airworthiness of jump aircraft by developing and distributing “guidance materials to assist operators in implementing effective aircraft inspection and maintenance quality assurance programs”. The NTSB must have deemed the guidance materials provided by the joint efforts of the FAA and the USPA to be adequate. However, the investigation of the accident at the Oahu Parachute Center in 2019 revealed that the accident aircraft was not properly maintained or airworthy and that condition contributed to the eleven fatalities.

The guidance materials either weren’t adequate and / or the dissemination of those materials was ineffective in preventing the accident in Hawaii or any of the other eighty accidents that were the result of non-airworthy aircraft since 2008. In the accident report for the crash in Hawaii the NTSB failed to cite either of those two facts as being contributing factors for any of the eleven fatalities.

Recommendation A-08-069 is the same as A-08-64. In the USPA’s Official Correspondence dated April 7, 2011, Ed Scott, Executive Director wrote that the USPA, “. . . took some bold steps that went above and beyond the actions called for by A-08-09 (sic). As I expressed to you at the end of the NTSB hearing on September 16, 2008, USPA was going to use this opportunity to educate and assist our operators with meeting the aircraft inspection and maintenance requirements of the FAA. The cornerstone of our efforts included a revision to our program by which skydive operators affiliate with USPA. Affiliation now requires submittal of a new form that solicits information about the specific inspection program that each jump aircraft is subject to. Operator acceptance was universal. USPA is looking forward to advising the NTSB of our efforts with respect to Safety Recommendations A08-70, A-08-73, and A-08-74 which all await FAA publication of revised Advisory Circular 105-2D.”

The NTSB found that the USPA’s response was beyond what was recommended so they classified the recommendation as being, “CLOSED - EXCEEDS RECOMMENDED ACTION”.

The acts of developing and distributing guidance materials, revising their programs, submission of the new form and universal acceptance by the operators failed to prevent the accident in Hawaii or any of the other eighty accidents that were the result of non-airworthy aircraft since 2008.

NTSB Recommendations to Affect Piloting in Report SIR-08/01

Recommendation A-08-065 seeks to improve piloting by requiring jump operators to develop initial and recurrent pilot training programs.

Recommendation A-08-066 seeks to improve piloting by requiring jump operators to develop initial and recurrent pilot testing in order to verify that piloting skills have been retained. The first sentence in Section 3, “Pilot Training and Proficiency Issues”, of the 2008 Special Report, the NTSB wrote:

“A disturbing common denominator in nearly all of the accidents reviewed is that the pilots, most of whom were commercial or airline transport pilots, were deficient in basic airmanship tasks.”

Initial and recurrent training and testing of pilot proficiency is needed. The facts associated with scores of fatal accidents clearly indicate that, but, as the FAA points out to the NTSB in their Official Correspondence included in the Recommendation, more regulation may not be.

Recommendation A-08-067 seeks to improve piloting by “revising the guidance materials contained in Advisory Circular 105 2C, Sport Parachute Jumping, to include guidance for parachute jump operators in implementing effective initial and recurrent pilot training.” AC 105 2D included advice to train and test pilot proficiency.

The pilot of the Beech King Air that crashed in Hawaii lacked training and proficiency so revision of the Advisory Circular didn’t have the desired effect on him or the Oahu Parachute Center drop zone operator or any of the drop zone operators whose operations were among the eighty accidents that were the result inadequate pilot training or proficiency since 2008.

Recommendation A-08-070 seeks to improve piloting by having the USPA distribute the revised Advisory Circular (105-2D) to their members and, “encourage adherence to its guidance”, “. . . in implementing effective initial and recurrent pilot training and examination programs.” In their Official Correspondence of February 13, 2012 the USPA stated that they complied with the recommendation by emailing the AC to its members and by publishing two articles on the subject in Parachutist Magazine. They wrote that the, “USPA has also urged operators to enhance their jump pilot training regimen and has developed and included in the 2011 USPA Skydiving Aircraft Operations Manual and the Jump Pilot Training Syllabus additional guidance on pilot training and proficiency.” The NTSB found that the USPA’s response was beyond what was recommended so they classified the recommendation as being, “CLOSED - EXCEEDS RECOMMENDED ACTION”.

However, distributing the Advisory Circular and the other acts that the NTSB deemed in excess of the recommendation weren’t sufficient to have the desired effect on the pilot of the Beech King Air that crashed in Hawaii or the Oahu Parachute Center operator or any of the drop zone operators whose operations were among the eighty accidents that were the result of inadequate pilot training or proficiency since 2008.

NTSB Recommendations to increase FAA Oversight and Surveillance in SIR-08/01

Recommendation A-08-068 was to was to improve the airworthiness of jump aircraft by requiring the FAA to conduct “direct surveillance of parachute jump operators to include, at a minimum, maintenance and operations inspections.” Four of the twelve recommendations in the Special Investigation Report were for changes to regulations. Presumably the three recommendations that were classified as, “CLOSED - UNACCEPTABLE ACTION”, would have involved changes to 14 CFR Part 91. This one however was simpler and was accomplished through revision to Federal Orders 8900.1, “Flight Standards Information Management System,” Volume 6, Chapter 11, Section 5 and Order 1800.56, “National Flight Standards Work Program Guidelines”. In the accident report on the event in Hawaii, the FAA noted that other Federal Orders contradict the revised order intended to save skydivers' lives. Section 1.9.2, “Federal Aviation Administration Oversight” of the accident report, states, in part:

“Inspectors were to perform annual inspections for each parachute jump operation within a FSDO’s jurisdiction, including a parachute jump inspection and ramp inspections. The FSDO operations inspector who conducted these inspections at OPC stated that the surveillance activities that the FAA required for parachute jump operations were not extensive and that the FAA had limited oversight of those operations."

FAA Orders 8300.10 and 8700.1, Joint Flight Standards Information Bulletin for Airworthiness (FSAW 93-09) and General Aviation (FSGA 93-02), Parachutists Regulatory Status, dated January 25, 1993, stated the following:

"Federal Aviation Regulations dealing with sport parachute operations were promulgated primarily to ensure protection of other users of the National Airspace System and the general public from sport parachuting activities. It has been determined that parachute jumping is a sport activity and, as such, should be subject to the FARs only to the extent necessary to protect others . . . Aviation safety inspectors . . . having surveillance responsibilities of sport parachute activities should be aware that it is the FAA position that parachutists should not be considered passengers when evaluating the regulatory compliance status of such operations.”

THE IMPLICATION IS THAT AN INSPECTION THAT WOULD HAVE REVEALED THE EXTENT OF THE NON-AIRWORTHY ASPECTS OF THE ACCIDENT AIRCRAFT OR THE PILOT’S LACK OF TRAINING AND PROFICIENCY WAS NOT REQUIRED AND SUCH DEFICIENCIES ARE NOT NECESSARILY AN ASPECT OF THE INSPECTION, “WHEN EVALUATING THE REGULATORY COMPLIANCE STATUS OF SUCH OPERATIONS”.

This response is quite profound. This recommendation was classified as “CLOSED -ACCEPTABLE ACTION” and inspections have taken place since 2008. However, the FAA’s position, since 2019, at least, is that skydivers are not passengers. Therefor, the inspections and the added surveillance provided by the FAA, are NOT required to have the practical outcome envisioned by the NTSB’s recommendation.

NTSB Recommendations to Increase Survivability Through Improved Restraints in Report SIR-08/01

Recommendations A-08-071 , A-08-072 & A-08-073 are three of the subjects of the first section of Appendix A of the Special Investigation Report, SIR-08/01. A-08-071 and A-08-073 were both for conducting research to determine the most effective dual-point restraint systems for parachutists. A-08-072 recommended revising Advisory Circular 105-2C, Sport Parachute Jumping, to include guidance information about these systems.

Recommendation A-08-074 , the fourth subject of the first section of Appendix A, recommended that the USPA educate their members on the findings and encourage them to use the most effective dual-point restraint systems.

The second section of Appendix A of SIR-08/01 includes seven safety recommendations (three to the FAA and four to the USPA) regarding parachutists’ seating and restraints that were issued on February 17, 1994. As with the recommendations regarding restraints made fourteen years later, and with the advise and guidance and dissemination that has been provided to this day, many drop zones have still not realized the practical effects of what any of these recommendations were intended to provide. Skydivers at those drop zones are no more likely to survive crashes then they were twenty-eight years ago.

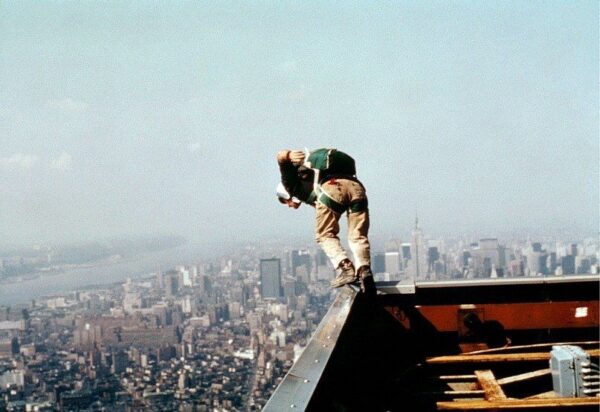

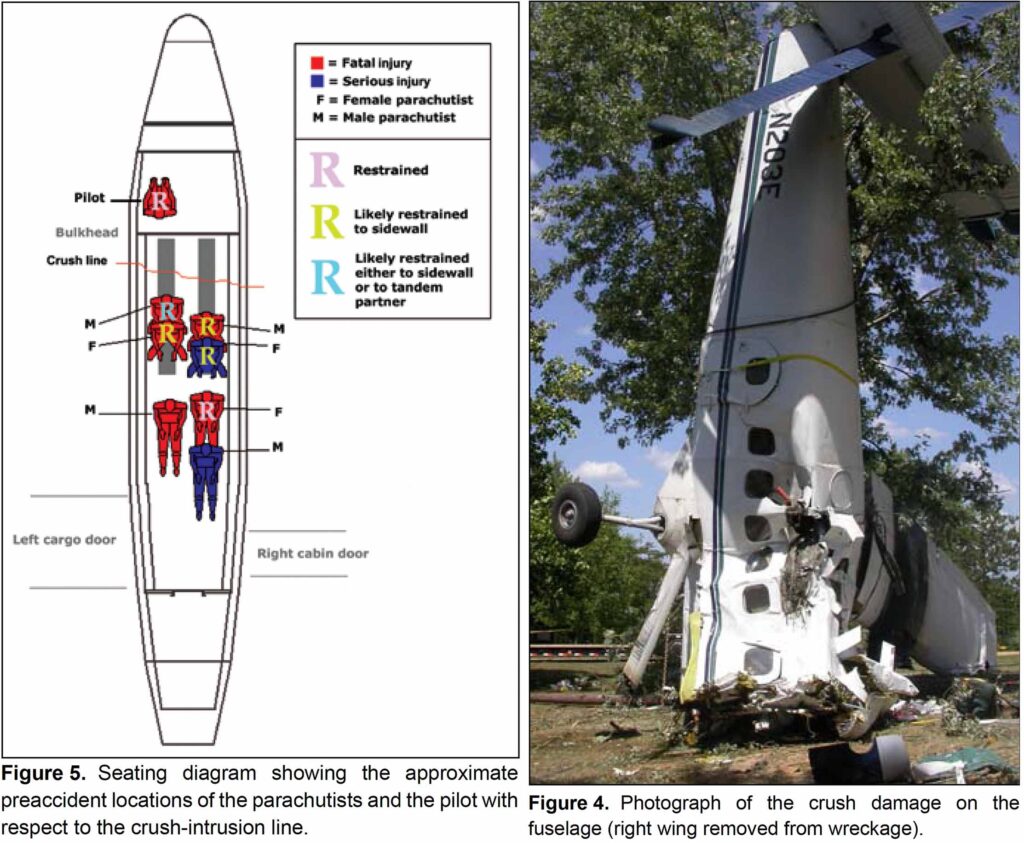

The images below are from Section, “3.1 Accident Survivability”, in the report for the crash in Sullivan, Missouri on July 29, 2006. The docket for that accident includes the injury report for the two survivors and the six who perished. Although the crash was survivable, with G forces peaking at 19.7, their injuries were very extensive. This was due to the fact that, although restrained, the single-point system that was used allowed, “harmful movement, such as large translational and rotational motion”. This type of restraint is still used in many skydiving aircraft, which is not the one that is described in great detail in Appendix 3 of the current Advisory Circular for Sport Parachuting, AC 105-2E.

Four Decades of Accidents, Reports and Recommendations

The accidents cited in SIR-08/01 happened up to forty-two years ago and many of the same recommendations that were made after those accidents were only reiterated in 2008 and have been unresolved for decades. It took almost seven years for all these recommendations to be “closed” and the NTSB considered the resolution for three of twelve to be “Unacceptable”.

History repeats itself. Specifically, the repetition is in the investigations and the responses to them by the FAA, the USPA and skydivers. The FAA’s response is consultation with the USPA, Advisory Circulars (which do not have the force of law) and increased surveillance, which has turned out to be ineffective and temporary. The historical response from the USPA is consultation with the FAA and attempts to influence the behavior of drop zone operators by disseminating safety information derived from the investigations. Historically, skydivers themselves have done nothing.

What if . . . ?

Since 1968 when the original Advisory Circular for Sport Parachuting was issued the USPA has tried to solve the problem with jump plane accidents from the top. They and the FAA have advised and guided and published articles and sent letters and emails to drop zone operators, pilots and skydivers for decades. Surely, that has had positive effect, but just as surely, those efforts have not been enough.

“Safety Culture” is a term that was first coined while investigating what happened at the Chernobyl meltdown in 1986. It existed at refineries, the DuPont Company and elsewhere previously, but didn’t exist hardly anywhere in the Soviet Union at the time.

All truly successful drop zones have a thriving safety culture, an atmosphere where every jumper knows that safety is the most important concern for everyone and where every jumper is welcome to contribute to it. “Safety Climate” has the same meaning and is probably a better metaphor because it doesn’t blow in from Fredericksburg, VA or Washington DC. It’s always in the air in the hangars, the landing areas, on the runways and around the bon-fires in places like Mokuleia, Hawaii, Ridgely, Maryland and Sullivan, Missouri.

Normalization of Deviance is another concept and term that was first used while investigating a tragedy. Coincidentally that event happened in the same year as the Chernobyl meltdown. A sociologist came up with it while analyzing the Space Shuttle Challenger accident. In the Shuttle Program waivers and deviations became normal. The Commission who studied that accident determined that condition to be a proximate cause of the accident. That condition hasn’t been cited in any of these NTSB accident investigations. That could be because, despite the fact that safety is their primary concern, “safety culture”, for the conduct of skydiving and even flight operations can’t exist at the NTSB or the USPA.

The reason why that is true is simply to do with the definition of the term. A paper commissioned by the FAA titled, “The Safety Culture Indicator Scale Measurement System (SCISMS)”, provides one. The authors claimed that, “SCISMS has verified its utility and reliability as a system measurement tool”, so their definition has to be a pretty good. After all, you can’t apply metrics to something that isn’t well defined. Their definition of safety culture is necessarily long, but not complicated:

"Safety culture is typically defined as a group-level construct with various dimensions pertaining to the occupation studied. Safety culture has previously been defined as the enduring value and prioritization of worker and public safety by each member of each group and in every level of an organization. It refers to the extent to which individuals and groups will commit to personal responsibility for safety; act to preserve, enhance and communicate safety information; strive to actively learn, adapt and modify (both individual and organizational) behavior based on lessons learned from mistakes; and be held accountable or strive to be honored in association with these values (von Thaden, Kessel & Ruengvisesh, 2008, adapted from Wiegmann, Zhang, von Thaden, Sharma & Mitchell, 2002:8). This definition combines key issues such as personal commitment, responsibility, communication, and learning in ways that are strongly influenced by processes instantiated by upper-level management, but also influence the behavior of everyone in the organization (cf. Wiegmann, et. al, 2004)."

NTSB Investigators and USPA Directors, in their roles as investigators and directors, don’t, “commit to a personal responsibility for safety”, at drop zones, because they physically can’t. They aren’t there. They can’t, “be held accountable or strive to be honored in association with these values.” As investigators and directors they aren’t members of the cultural group to whom they could be held accountable or by whom they could be honored. USPA directors are skydivers and when they are at a drop zone to jump they are absolutely a part of that drop zone’s safety culture, if there is one. As Directors they absolutely are not.

When the policies regarding the safety of flight operations are made solely by the owner, one pilot and the USPA Safety and Training Advisor, as is often the case, there is no safety culture. Three individuals, particularly those who have inherent conflicts of interest, shouldn’t be the only ones to establish a safety culture. At those drop zones all the skydivers rely on those three to make the right choices for everyone’s survival but unless everyone at risk actively participates in those decisions, the culture, if there is one, is established without them. Because of that, most drop zone’s flight operations programs would probably receive a very low grade as measured by SCISMS.

What if the drop zone owner, the one who signs the pledge with which he promises to follow the rules and operate safely, enlisted the help of well qualified volunteers to oversee their own safety? Nothing would be more likely to result in the safety culture that the owner should promote and embrace. The diligence that such a committee could apply could ensure that the sound recommendations of the NTSB and the FAA’s thoughtful advise was followed, without Federal regulation. Tens of thousands of USPA members would be the pool of vitally interested men and women willing to participate in such a program. Many hundreds among them are fully qualified to do so. Read the post, Proposal for Reform, for the thumbnail of the program.

Skydivers and the USPA need to finally get in front of this before another NTSB Special Report comes out, although it’s probably too late. Indications are that such a report is already being written. It will refer to all the accidents before and since 2008 and it will point out that past recommendations haven’t been effective. It may also recognize that since the invention of tandem equipment, skydiving has become an amusement available to young couples like Brian and Ashley Weike, who didn’t realize that they weren’t passengers on an airplane or that they shouldn’t have placed their trust in anyone at that drop zone or the USPA’s process for approving their affiliates.

Some of the authors might also have in mind the fact that many tandem pilots and even USPA Safety and Training Advisors are BASE jumpers. It’s highly doubtful that any inspector or writer employed by the NTSB regards BASE jumping, as safe or even rational, yet USPA membership, even employment and positions of authority, isn’t contingent on not engaging in highly unsafe behavior.

Since their report will include what happened in Hawaii in 2019 it will further document the deaths of Brian and Ashley, and others. At some point someone in authority will get it into his head that, for decades the USPA’s methods of dealing with this hasn’t worked. If fundamental changes aren’t undertaken, actual regulation will follow. Perhaps it should.

Recommendations and Advice Read More »